TL;DR

We’ll focus on the extensibility points of the C# compiler to customize the behavior of async methods and task-like types. As result, we will be able to write linear, concise, and composable code with the possibility to have control over task scheduling. 🤓

C# 💜 patterns

Numerous C# features are based on duck-typing and patterns inferred by the compiler. Basically, it means that a developer doesn’t need to implement interfaces or inherit classes explicitly to achieve some pluggable behavior. Instead, we could follow some well-known conventions inferred by the compiler to plug or glue some functionality together. Duck-typing is great when strongly-typed approach impedes too many limitations or you want to keep your code clean and tidy. So if you’ve got a pattern right, than, the compiler will do its magic and generate some code for you. Let’s see examples of such patterns in C#.

| Pattern | How to use | |

|---|---|---|

| Foreach | Implement GetEnumerator method to make you custom type work with foreach. |

|

| LINQ Queries | Implement SelectMany, Select,Where, GroupBy, OrderBy, ThenBy, Join. C# compiler creates a series of method calls. As long as these methods are found, you are good. |

|

| Deconstructors | Implement the Deconstruct method with a bunch out parameters. The result of deconstruction could be consumed as ValueTuple or as separately initialized variables. |

|

| Dynamic | The C# compiler invokes a whole reflection machinery which by default can invoke methods, properties, and fields. As soon as the object implements IDynamicMetaObjectProvider the object gets runtime control on what is invoked. |

|

| Async/Await | The only thing required is a GetAwaiter method which returns an object having an IsComplete and GetResult() method and implementing the INotifyCompletion interface. |

|

Examples

Before we delve into the main part, I would like to warm you up and provide some examples of how C# compiler infers patterns in various cases.

Foreach

Usually, we implement IEnumerable to support collection-like behavior. As result, it is possible to use foreach over user-defined types. But, in order for type to be consumed by foreach you just need to implement GetEnumerator method. Beside that, C# 9 introduces nice little feature. You can iterate over System.Range by implementing extension method. This enables a bunch of new opportunities, e.g.:

public static IEnumerator<T> GetEnumerator<T>(this System.Range range) => enumerator;

// Usage

foreach (var i in 1..10) {}

LINQ Queries

Generate permutations for a list of words and write LINQ quires over it. See full version on Github: PermutationsSource.cs.

// Implementation

public class PermutationsSource

{

//...

public IEnumerable<T> SelectMany<T>(

Func<PermutationsSource, IEnumerable<string>> selector, Func<PermutationsSource, string, T> resultSelector) =>

selector(this).Select(i => resultSelector(this, i));

public PermutationsSource Select(Func<PermutationsSource, PermutationsSource> selection) => selection(this);

//...

}

// Usage

var q = from ps in new PermutationsSource("test", "test", "new")

from perm in ps.Permute()

where perm.Length < 4

select perm;

Debug.Assert(q.Count() == 6);

Deconstructors

Besides tuples, you can deconstruct custom types that have Deconstruct method implement as class member or extension method.

public class Person

{

public string FirstName { get; }

public string LastName { get; }

public int Age { get; }

public Person(string fName, string lName, int age) =>

(FirstName, LastName, Age) = (fName, lName, age);

public void Deconstruct(out string fName, out string lName) =>

(fName, lName) = (FirstName, LastName);

public void Deconstruct(out string fName, out string lName, out int age) =>

(fName, lName, age) = (FirstName, LastName, Age);

}

// Usage

var p = new Person("John", "Doe", 42);

(string firstName, _) = p;

var (x,_, z) = p;

Async/Await

You can implement simplistic awaitable/awaiter pattern based on extension methods. Like this:

public static TaskAwaiter GetAwaiter(this IEnumerable<Task> tasks) =>

TaskEx.WhenAll(tasks).GetAwaiter();

// Usage

await from url in urls select DownloadAsync(url);

🚀 Let’s see how we can use this in something, that I call logical micro-threading.

Problem: Largest series product

Occasionally, I use coding platforms to practice my craft. I really like the idea of doing Katas to hone coding skills, because you truly know something when you’ve implemented it and get hands-on experience. Katas is part of the thing. 🐱👤

A code kata is an exercise in programming which helps programmers hone their skills through practice and repetition.

Let’s solve this one: exercism.io/tracks/csharp/exercises/largest-series-product.

Given a string of digits, calculate the largest product for a contiguous substring of digits of length n.

The problem itself is really straightforward and we could solve it by iterating over the input array and calculating the local maximum every time the window has a length of a given value (span).

Here is my first take on it: largest-series-product/solution.

var max = 0;

var curr = 1;

var array = ToDigits(digits);

var length = array.Count;

int start = 0, end = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < length; i++)

{

end = i;

if (array[i] == 0)

{

start = i + 1;

end = start;

curr = 1;

continue;

}

var full = end - start >= span;

if (full)

{

curr /= array[start];

curr *= array[i];

start++;

}

else

curr *= array[end];

max = curr > max && (end - start + 1 == span) ? curr : max;

}

return max;

I hate to read code like this 🤮. It takes you quite some time and effort to really figure out what is going on. With great confidence, we can describe this code as write-only.

Write-only code code is source code so arcane, complex, or ill-structured that it cannot be reliably modified or even comprehended by anyone with the possible exception of the author.

Let’s formulate how we could tackle the complexity of a relatively simple problems in utterly hyperbolical manner.

My goal is to share with you the technique. I deliberately chose a simple problem so we could try to understand the micro-threading approach without delving into details.

Micro-threading

C# 5 language made a huge step forward by introducing async/await. Async/await helps to compose tasks and gives the user an ability to use well-known constructs like try/catch, using etc. A regular method has just one entry point and one exit point. But async methods and iterators are different. In the case of async method, a method caller get the (e.g. Task-like type or Task) result immediately and then “await” the actual result of the method via the resulting task-like type.

Async machinery

Methods marked by async are undergoing subtle transformations performed by the compiler. To make everything work together, the compiler makes use of:

- Generated state machine that acts like a stack frame for an asynchronous method and contains all the logic from the original async method

- AsyncTaskMethodBuilder<T> that keeps the completed task (very similar to TaskCompletionSource<T> type) and manages the state transition of the state machine.

- TaskAwaiter<T> that wraps a task and schedules continuations of it if needed.

- MoveNextRunner that calls IAsyncStateMachine.MoveNextmethod in the correct execution context.

The fascinating part is you use extensibility points the C# compiler provides for customizing the behavior of async methods:

- Provide your own default async method builder in the

System.Runtime.CompilerServices namespace. - Use custom task awaiters.

- Define your own task-like types. Starting from C# 7.2.

Later, we will see how the last two options could be used in more detail.

Let’s get back to kata problem, shall we?

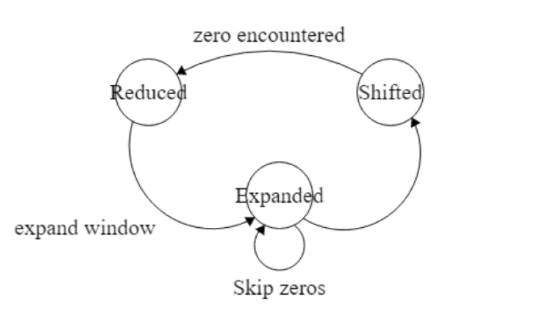

If we take a look from the different angle we can spot different states in which the sliding window can be: “reduced”, “expanded”, and “shifted”.

So, the idea is to move the window from left to right and calculate local product every time the window is “expanded” or “shifted”.

Solution of the largest series product with awaitable/awaiter patten

My goal is to come up with the solution write highly composable and linear code and at the same time have control of how building blocks are executed and scheduled.

The solution consists of next building blocks:

$ tree -L 2 lib

lib

├── Core

│ ├── AsyncTicker.cs

│ ├── IStrategy.cs

│ ├── StrategyAwaiter.cs

│ ├── StrategyBuilder.cs

│ ├── Strategy.cs

│ ├── StrategyExtensions.cs

│ ├── StrategyResult.cs

│ ├── StrategyStatus.cs

│ └── StrategyTask.cs

├── LargestSeriesProductV2.cs

├── lib.csproj

└── StrategyImplementations

├── ChaosWindowStrategy.cs

├── ExpandStrategy.cs

├── MultipleSlidingWindowsStrategy.cs

├── ShiftStrategy.cs

├── SkipStrategy.cs

├── SlideStrategy.cs

├── SlidingWindowStrategy.cs

└── Solver.cs

2 directories, 19 files

Full source code: /exercism-playground/csharp/largest-series-product

Core

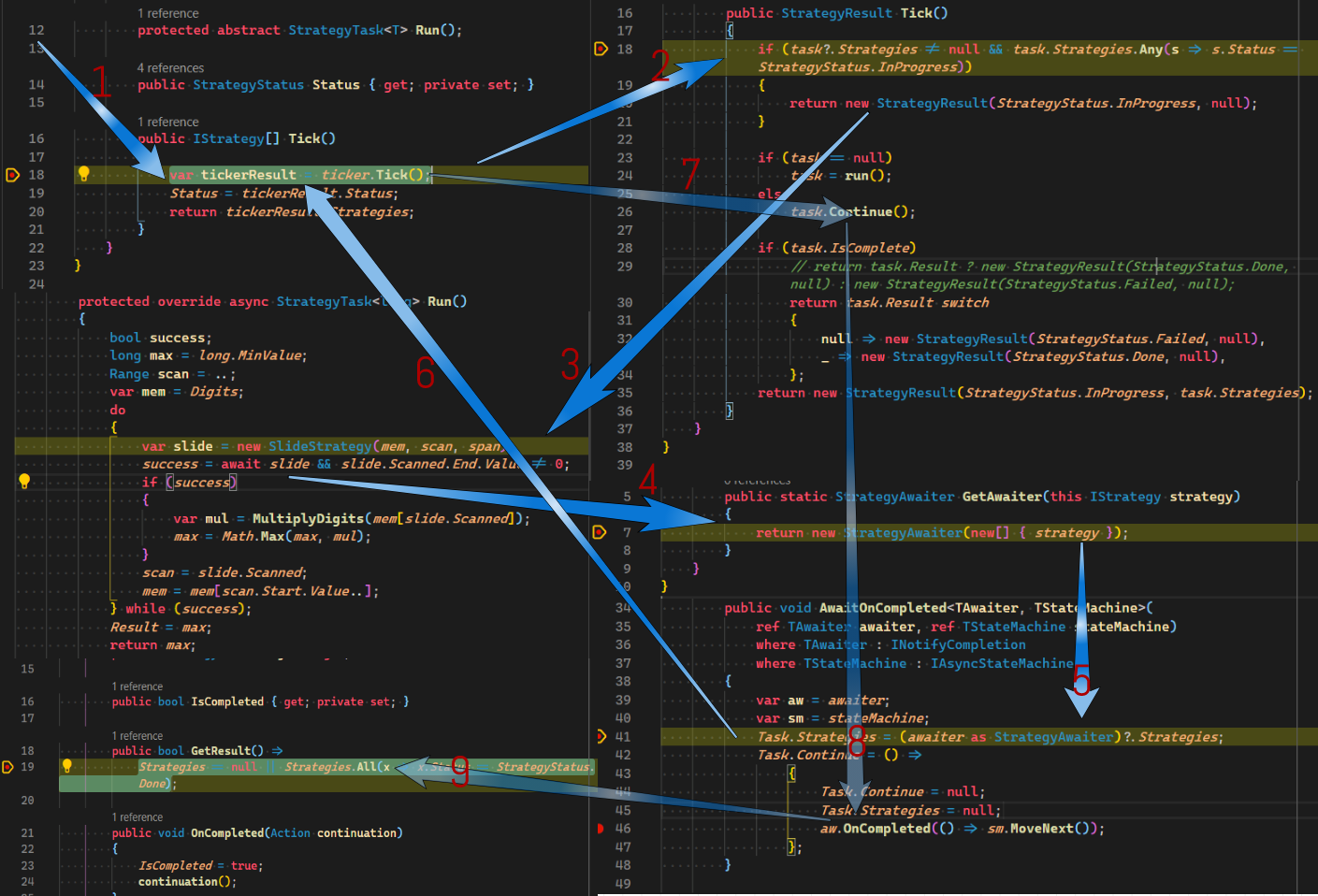

In order to use async/await for task-like types we need to introduce a bunch of extensibility points.

A strategy represents a discrete and composable algorithm:

public interface IStrategy

{

StrategyStatus Status { get; }

IStrategy[] Tick();

}

public class StrategyResult

{

public StrategyStatus Status { get; set; }

public IStrategy[] Strategies { get; set; }

}

public enum StrategyStatus { InProgress, Done, Failed }

We want to make it awaitable and you do it like this await myAwesomeStrategy

StrategyExtensions.cs:

public static class AwaitableExtensions

{

public static StrategyAwaiter GetAwaiter(this IStrategy strategy) =>

new StrategyAwaiter(new[] { strategy });

}

As mentioned before, C# compiler could do its magic if we implement awaitable/awaiter patter.

public class StrategyAwaiter : INotifyCompletion

{

public StrategyAwaiter(IStrategy[] strategies)

{

Strategies = strategies;

}

public IStrategy[] Strategies { get; }

public bool IsCompleted { get; private set; }

public bool GetResult() =>

Strategies == null || Strategies.All(x => x.Status == StrategyStatus.Done);

public void OnCompleted(Action continuation)

{

IsCompleted = true;

continuation();

}

}

public class StrategyTask

{

private readonly IStrategy[] strategies;

public StrategyAwaiter GetAwaiter() =>

return new StrategyAwaiter(strategies);

}

[AsyncMethodBuilder(typeof(StrategyTaskBuilder<>))]

public class StrategyTask<T>

{

public IStrategy[] Strategies { get; set; }

public T Result { get; set; }

public bool IsComplete { get; set; }

public Action Continue { get; set; }

}

public class StrategyTaskBuilder<T>

{

// skipped for brevity

}

That’s a lot, I know. But, bare with me, I will show how it works:

- Driver do the

.Tick() AsyncTickerruns a fresh strategy/task. (run())- Code executes normally until first

await GetAwaiterunwraps task-like typeAsyncMethodBuilderinitializes state machineAsyncTickerruns continuation (continue())stateMachine.MoveNext()is invoked- If

StrategyTaskis completed, the result is returned and control flow is resumed

I suggest you to spin up the debugger and investigate on your own 😉.

Let’s say we want to define a top-level strategy that is based on sliding windows giving us a valid span for every type we await a sub-strategy to slide:

// SlidingWindowStrategy.cs

protected override async StrategyTask<long> Run()

{

bool success;

long max = long.MinValue;

Range scan = ..;

var mem = Digits;

do

{

var slide = new SlideStrategy(mem, scan, span);

success = await slide && slide.Scanned.End.Value != 0;

if (success)

{

var mul = MultiplyDigits(mem[slide.Scanned]);

max = Math.Max(max, mul);

}

scan = slide.Scanned;

mem = mem[scan.Start.Value..];

} while (success);

Result = max;

return max;

}

A valid slide could look something like this:

// SlideStrategy.cs

protected override async StrategyTask<bool> Run()

{

var skipped = false;

var newSource = Scanned;

if (source.Span[0] == 0)

{

var skip = new SkipStrategy(source);

skipped = await skip;

Scanned = skip.Scanned;

if (skipped && newSource.End.Value == 0 && !newSource.End.IsFromEnd)

return false;

}

if (Scanned.End.Value - Scanned.Start.Value != span)

{

var expand = new ExpandStrategy(source[newSource.Start.Value..], span);

var expanded = await expand;

Scanned = expand.Scanned;

return expanded;

}

else

{

var shift = new ShiftStrategy(source, span);

var shifted = await shift;

Scanned = shift.Scanned;

return shifted;

}

}

And the building blocks:

// ExpandStrategy.cs

protected override async StrategyTask<bool> Run()

{

var end = 0;

var start = 0;

while (end < source.Length && (end - start) < span)

{

if (source.Span[end] == 0)

{

var skip = new SkipStrategy(source);

var skipped = await skip;

start = skip.Scanned.Start.Value;

if (!skipped)

return false;

}

Scanned = start..(end + 1);

end++;

}

return true;

}

// ShiftStrategy.cs

protected override async StrategyTask<bool> Run()

{

if (span >= source.Length)

{

Scanned = default;

return false;

}

if (source.Span[span] == 0)

{

var expand = new ExpandStrategy(source[(span + 1)..], span);

var expanded = await expand;

var shiftedRange = (expand.Scanned.Start.Value + span)..(expand.Scanned.End.Value + span);

Scanned = shiftedRange;

return expanded;

}

Scanned = 1..(span + 1);

return true;

}

// SkipStrategy.cs

protected override async StrategyTask<bool> Run()

{

var cnt = 0;

var wasSkipped = false;

while (source.Span[cnt] == 0)

{

wasSkipped = true;

Scanned = ++cnt..;

}

return wasSkipped;

}

And now, when we have the solution assembled, we can write a “Driver” code to trigger task machinery. Control flow is returned to the driver every time we await something. This means, that we can change the way strategies are scheduled without modification of the actual algorithm. We may say that scheduling is moved out to a separate layer and adheres Open-Closed Principle (OCP) in this regard.

Having this layer we can enhance the solution with:

- Interception logic

- Fine-grained control over strategy scheduling

- Cancellation logic without the necessity to throw an

Exception

public class Solver

{

private void SequentialScheduling<T, K>(T strategy) where T : Strategy<K>

{

RecursiveTick(strategy: strategy, indentation: 0);

}

// The simplest approach is to make use of thread pool to introduce concurrency, but if we wanted to

// we would implement a scheduler that has complete supervision over control flow

private void ThreadpoolScheduling<T, K>(params T[] strategies) where T : Strategy<K>

{

var tasks = strategies.Select(t => Task.Run(() => RecursiveTick(t, 0)));

Task.WaitAll(tasks.ToArray());

}

public bool RunDriver<T, K>(params T[] strategies) where T : Strategy<K>

{

SequentialScheduling<T, K>(strategies[0]);

return new StrategyTask(strategies).GetAwaiter().GetResult();

}

}

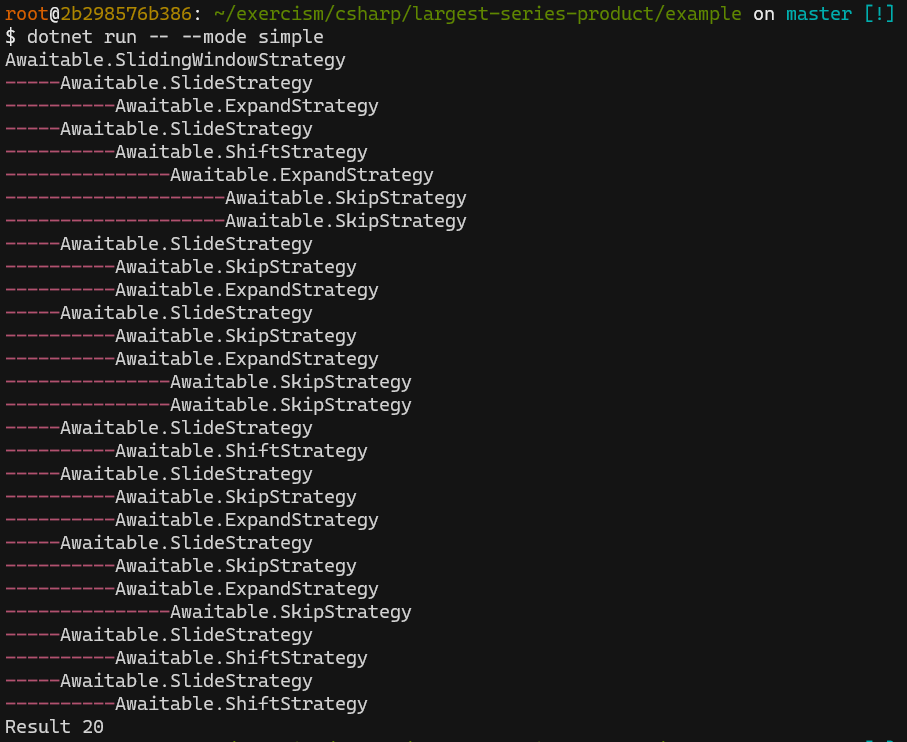

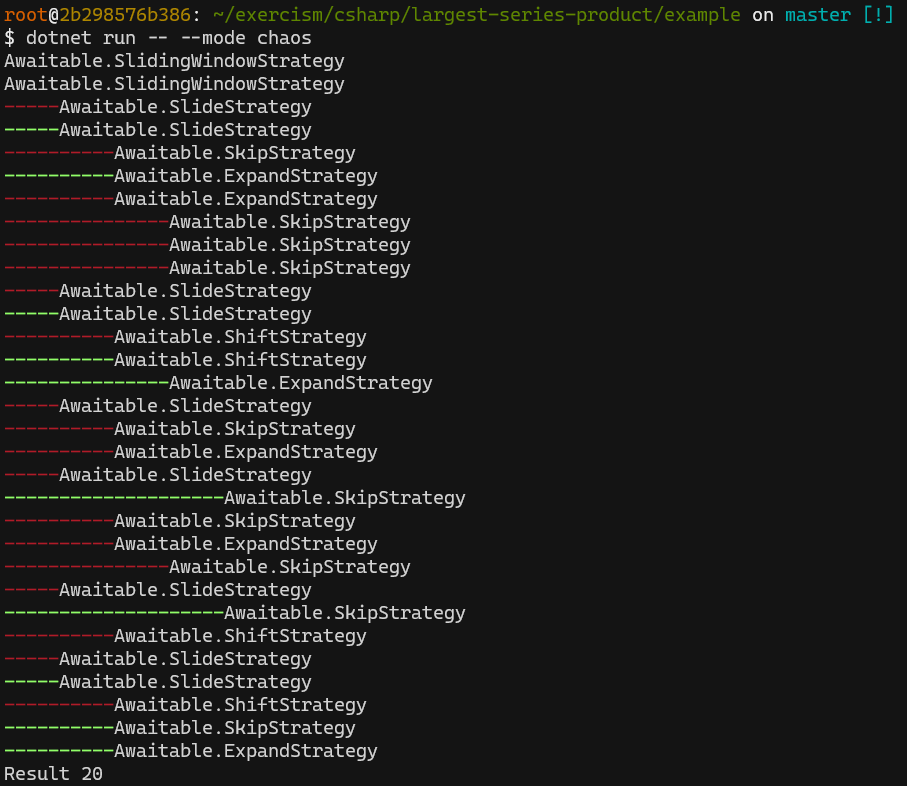

If we run we can see the output based on simple interceptor logic:

//entry point

var input = "290010345";

Solution.GetLargestProduct<SlideStrategy>(input, span: 2, Console.Out);

// GetLargestProduct

var strategy = new SlidingWindowStrategy(input, span);

solver.RunDriver<SlidingWindowStrategy, long>(strategy);

return strategy.Result;

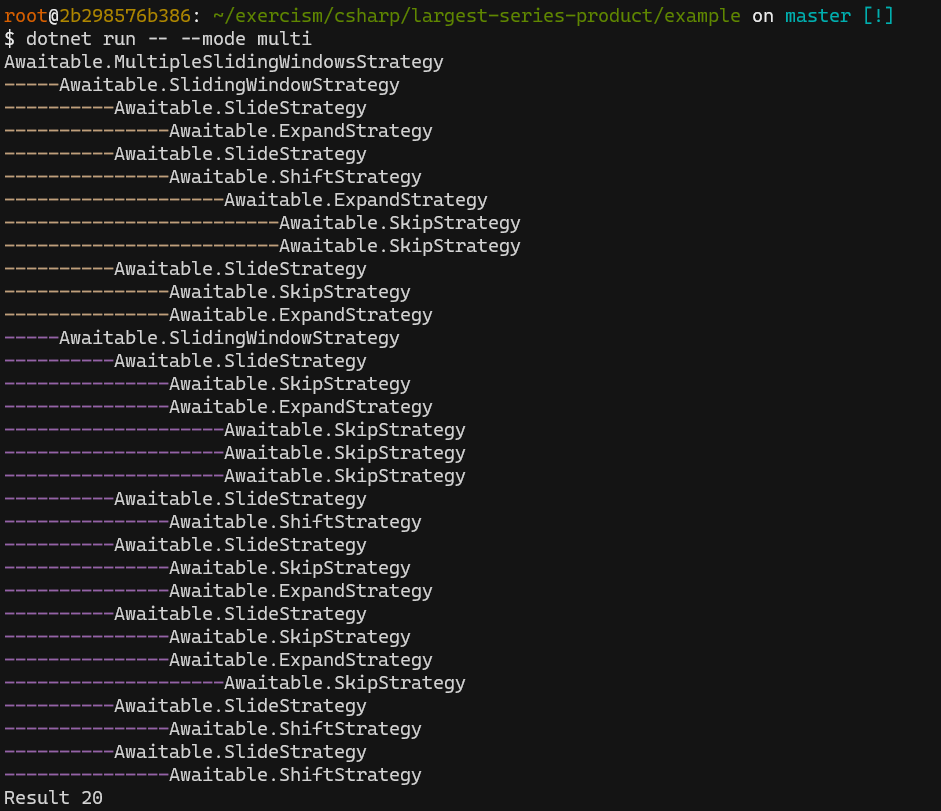

Let’s parallelize our solution by adding new strategy that will make use of existing building blocks:

//entry point

var input = "290010345";

Solution.GetLargestProduct<MultipleSlidingWindowsStrategy>(input, span: 2, Console.Out);

// GetLargestProduct

var strategy = new MultipleSlidingWindowsStrategy(input, span);

solver.RunDriver<MultipleSlidingWindowsStrategy, long>(strategy);

return strategy.Result;

// MultipleSlidingWindowsStrategy.cs

protected override async StrategyTask<long> Run()

{

var mid = Digits.Length / 2;

var strat1 = new SlidingWindowStrategy(Digits[..(mid + span)], 2);

var start2 = new SlidingWindowStrategy(Digits[(mid - span)..], 2);

await WhenAll(strat1, start2);

var res = Math.Max(strat1.Result, start2.Result);

Result = res;

return res;

}

protected StrategyTask WhenAll(params IStrategy[] strategies)

{

return new StrategyTask(strategies);

}

We could take another route and parallelize based on “Driver”

//entry point

var input = "290010345";

Solution.GetLargestProduct<ChaosWindowStrategy>(input, span: 2, Console.Out);

// GetLargestProduct

var mid = source.Length / 2;

var strategies = new SlidingWindowStrategy[]{

new SlidingWindowStrategy(source[..(mid + span)], span),

new SlidingWindowStrategy(source[(mid - span)..], span),

};

solver.RunDriver<ChaosWindowStrategy, long>(strategies);

return strategies.Select(s => s.Result).Max();

The beautiful thing is that we don’t need to change the actual implementation of the algorithm to have control over execution and scheduling. Which you may or may not find useful, but I find the approach interesting.

Conclusion

This is a tremendous over-engineering for such a simple problem. But I hope you’ve got this idea and how it could used to build custom async machinery.